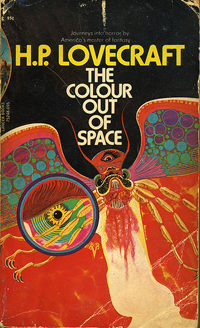

“The Color Out of Space” and “The Call of Cthulhu” are two stories that have already been reviewed in Seamus Cooper’s awesome series 12 Days of Lovecraft. He does a stellar job of summarizing these stories, and for that I refer you to him. I really enjoyed these two entries because my reactions to the stories were opposite Mr. Cooper, and helped me question why I liked “The Color Out of Space” despite it being a snoozefest, and why I was underwhelmed by “The Call of Cthulhu.”

I chose the “The Call of Cthulhu” because I couldn’t very well introduce myself to Lovecraft without experiencing this Elder God first hand. Perhaps it’s due to all the hype and cultists, but meeting the tentacled immortal was a bit underwhelming for me. I agree he is a horrible and frightful thing, but I have found that I am more intrigued by Lovecraft’s unique environments and madness than his actual mythos.

What I did like about “The Call of Cthulhu,” was the use of the narrator’s uncle’s research papers and clippings, as well as found artifacts and paintings, that documented the weird wave of Cthulhu’s call. While the narrator basically paraphrases all of it, the papers’ existence paired with the various sources and witnesses lends the story an authenticity necessary to winning the reader’s trust. He creates this authenticity also in “The Color Out of Space,” by witnesses, newspaper articles, and scientific data.

While I never considered the earlier characters of “The Outsider” and “The Hound” as unreliable, I certainly found them off-kilter and self-confined, relaying something that could only happen to them. The effects of “The Color Out of Space” and “The Call of Cthulhu” are more vast and varied, and while we still have a first person narrator, that narrator knows his words alone are not enough—for people to believe that a meteorite could hit earth and taint everything around it, or that there could be Gods older than the cosmos lurking beneath our seas, there needs to be material evidence.

What’s funny about Lovecraft’s authenticity, however, is that while he creates references and artifacts, his descriptions are less technical. The events in these stories are unique—things never seen before—so Lovecraft’s narrators struggle with description. This leads to a lot irksome clauses like:

What’s funny about Lovecraft’s authenticity, however, is that while he creates references and artifacts, his descriptions are less technical. The events in these stories are unique—things never seen before—so Lovecraft’s narrators struggle with description. This leads to a lot irksome clauses like:

“The colour, which resembled some of the bands in the meteor’s strange spectrum, was almost impossible to describe; and it was only by analogy that they called it colour at all.” (“The Color Out of Space”).

“Words could not convey it….” (“The Color Out of Space”).

“The Thing cannot be described….” (“The Call of Cthulhu”).

Typically, I consider phrases like the above lazy writing. If a writer cannot find the right words, then what is he doing? But Lovecraft plays with this and validates it with all the authenticating techniques mentioned earlier. For instance, in “The Color Out of Space,” he brings in scientific tests and conclusions that, while not honing in on what things are, eliminates what things are not.

As they passed Ammi’s they told him what queer things the specimen had done, and how it had faded wholly away when they put it in a glass beaker. The beaker had gone, too, and the wise men talked of the strange stone’s affinity for silicon. It had acted quite unbelievably in that well-ordered laboratory; doing nothing at all and showing no occluded gases when heated on charcoal, being wholly negative in the borax bead, and soon proving itself absolutely non-volatile at any producible temperature, including that of the oxy-hydrogen blowpipe. On an anvil it appeared highly malleable, and in the dark its luminosity was very marked. Stubbornly refusing to grow cool, it soon had the college in a state of real excitement; and when upon heating before the spectroscope it displayed shining bands unlike any known colours of the normal spectrum there was much breathless talk of new elements, bizarre optical properties, and other things which puzzled men of science are wont to say when faced by the unknown.

I also think Lovecraft is consciously waxing vague for the reader’s benefit—to allow the reader’s imagination to become engaged in “negative space.” In painting, negative space (the empty areas in and around figures and subjects) are equally important to composition as the positive. A prime example of this is in Turner’s Snow Storm—Steam Boat off a Harbor’s Mouth Making Signals in Shallow Water, where negative space is used to outline the action, forcing the viewer to pick out the maelstrom drama rather than have it “told to them” by realistic minutiae. In most cases, when given these implications, one’s imagination will take over and portray something more harrowing and gruesome than the artist could depict. I think this may be the source of Lovecraft’s mesmerism, because all of his descriptions of the weird are still vague enough to invite readers to carry on and build onto his foundations. And so they have.

I also think Lovecraft is consciously waxing vague for the reader’s benefit—to allow the reader’s imagination to become engaged in “negative space.” In painting, negative space (the empty areas in and around figures and subjects) are equally important to composition as the positive. A prime example of this is in Turner’s Snow Storm—Steam Boat off a Harbor’s Mouth Making Signals in Shallow Water, where negative space is used to outline the action, forcing the viewer to pick out the maelstrom drama rather than have it “told to them” by realistic minutiae. In most cases, when given these implications, one’s imagination will take over and portray something more harrowing and gruesome than the artist could depict. I think this may be the source of Lovecraft’s mesmerism, because all of his descriptions of the weird are still vague enough to invite readers to carry on and build onto his foundations. And so they have.

Well, it is the end of December, and I’m afraid I only got five stories in. That is obviously not enough for a big picture, but they were enough to whet my appetite. While I’m unsure whether I found the “quintessential” Lovecraft tale, I believe I can see where he diverged from his influences to become his own man. What I enjoyed most about these readings were the discoveries of subtle allusions I’ve missed out on and how connected he was to some of my favorite artists and writers. I am definitely a convert, and I’m looking forward to reading Lovecraft (especially reader’s recommendations!) more in the New Year and beyond.

S.J. Chambers is an articles editor at Strange Horizons. In addition to that fine publication, her work has also appeared in Fantasy, Bookslut, Yankee Pot Roast, and The Baltimore Sun’s Read Street blog. When she isn’t writing, she is excavating artifacts as Master Archivist for Jeff VanderMeer’s The Steampunk Bible.